A Cracking Deal for the UK, US, and Mauritius

Sovereignty, International Competition, and Dealmaking in the Indian Ocean

On October 3rd, the United Kingdom and the government of Mauritius announced a landmark deal to transfer sovereignty of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) centered on the Chagos Archipelago. Transfers of sovereignty are something that does not happen very often these days in internationally mediated agreements (i.e. in line with international law) - though perhaps more often than many think, see Tajikistan ceding 200 square kilometers of land to China in 2011, Egypt agreeing in principle to transfer the sovereignty of two Red Sea islands near Mohammed bin Salman’s fantastical NEOM project in 2016, or Sudan agreeing to the creation of South Sudan (admittedly after a long civil war) in 2011.

The development has hardly registered for US audiences – caught up in the presidential election’s final weeks, Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, and the potential for Tehran and Tel Aviv to plunge the Middle East into a wider conflict and spike a new energy market crisis. Yet it is predominantly a Washington story, both because the UK only retained the islands in 1961 under American pressure because they wanted to use them to host a submarine base in the Cold War with the Soviet Union, and because ever since the islands have played home to the US base and occasional black site Diego Garcia, today key in the ‘new cold war’ with the People’s Republic of China. The waters east of the Indian Ocean are key to force projection and rivalry over key Asian trade routes.

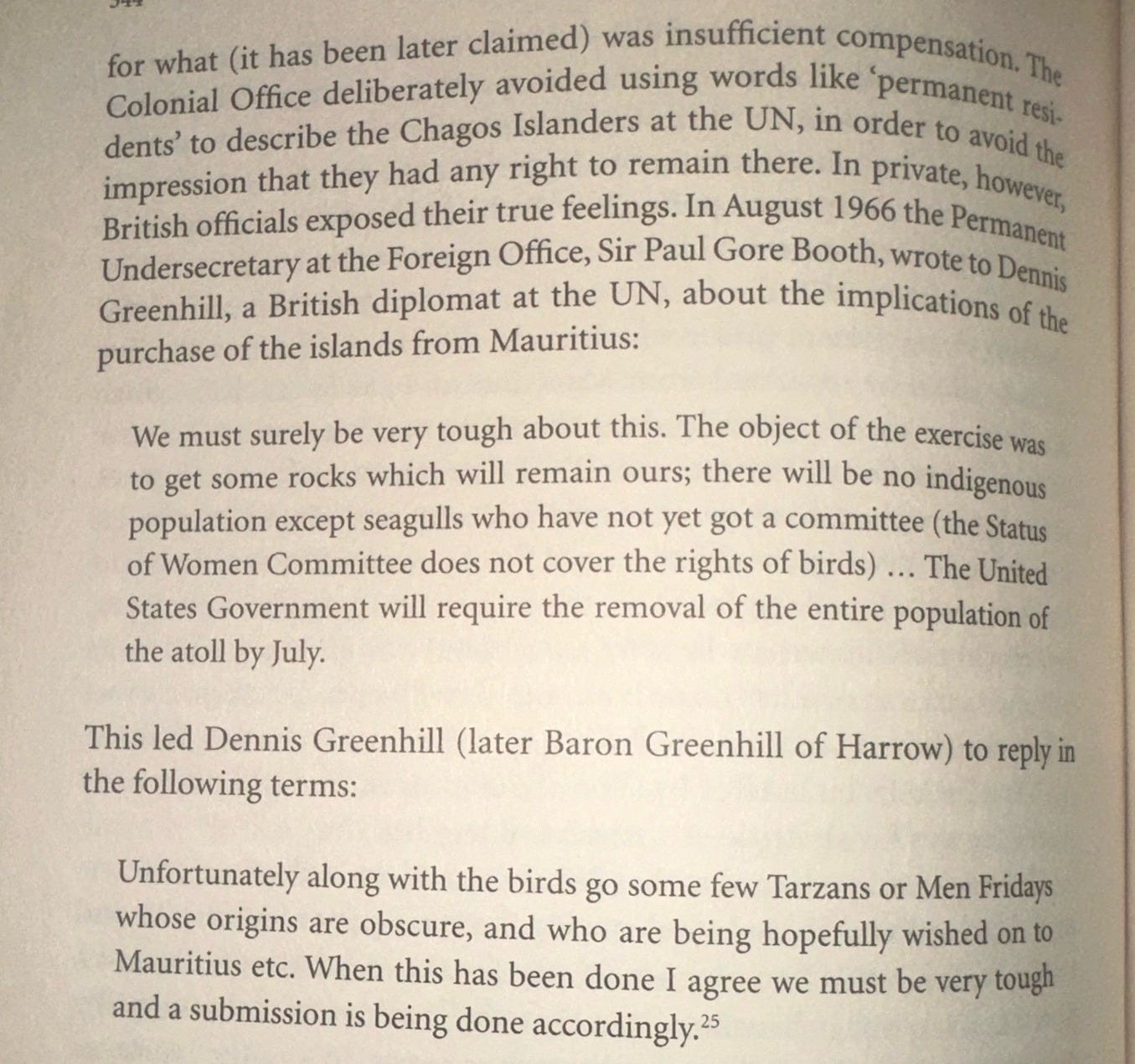

For American readers who – even if deeply interested in international affairs as I assume most readers of this blog are – may have missed the news entirely, here is a brief summary of the history of the dispute. The BIOT was separated from the territories in the Indian Ocean it governed as the process of decolonization after the Suez Crisis of 1956 accelerated the dismantling of the British Empire – something the UK enthusiastically pursued at the time. These included the Seychelles as well as Mauritius, which was independent in 1968. It was an Anglo-American Affair from the start, with Washington pushing for the islands to be de-populated and in 1974 Britain signed a secret agreement with the Nixon Administration that “allowed America to use the Chagos Islands effectively as its colony” to quote from Calder Walton’s Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire which covers the fiasco in detail on pages 343-345 (David Vine's Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia is also fabulous if you want a book-length read). A brief excerpt from Walton makes clear that Britain very much knew what it was getting up to in the depopulation effort.

Mauritius would repeatedly cry foul, despite receiving minor payments from the UK to help resettle residents (which also delayed long paying them). Mauritius more recently won support at the UN and in pressure and rulings by the UN, and in 2019 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) handed down a non-binding advisory opinion supporting Mauritius' claim.

In Britain, the story has dominated headlines. In Britain’s right wing-press – quaffing one of the last bottles of imperial nostalgia – warn that it could lead Keir Starmer’s three-month-old government to consider giving up the Falkland Islands to Argentina, who claim them as Las Malvinas. Or Gibraltar to Spain. But less hot-headed voices have also voiced concerns. The Economist has criticized the deal, coaching its criticism in language that some descendants of resettled Chagossians oppose the deal with Mauritius, whose main island is almost 2,000 kilometers south of the Chagos Islands. The United Kingdom’s main island, Britain, is of course over 6,900 kilometers away, and I don’t expect the Economist to suddenly apply this same logic to the claims of Palestinians descended from those expelled from their homes by Israeli forces living in Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon). The Economist also claims the talks have been going on for some time, however, and were launched by the previous Conservative Foreign Secretary, James Cleverly. Now running to lead the Tories following their worst election performance in modern history, he is vehemently against the new deal. That’s politics…

The other core area of argument is one rooted in English law, perhaps the only thing that Britain continues to export in large amounts.

The other core area of argument is one rooted in English law, perhaps the only thing that Britain continues to export in large amounts (Dubai and Kazakhstan have mock English law systems, staffed by British judges, efforts they launched in recent years while Hong Kong still retains them to provide a veneer of legitimacy amid the Communist Party’s domination of its political and legal systems. Advocates of this approach have cited a 2023 report published by the centrist Conservative think tank Policy Exchange that spelled out a highly legalistic argument against why Britain should consider transferring the islands’ sovereignty.

Now I am a legal realist, and think legal arguments typically contort to one’s preferred political position, but I also like reading the hifalutin arguments lawyers manage to get tied up in. Perhaps academic ones are less motivated by the coin, and more so by personal convictions, but I digress because my point is that they are irrelevant. The British critics of the deal – even those not claret-soaked in anger at the sun finally setting over what remains of the British Empire – not only ignore entirely the 1974 secret agreement but effectively already means the UK has not had sovereignty over the core portion of Diego Garcia, but also that there are genuine strategic benefits to the deal – which also explicitly leases Diego Garcia to the UK (and thus the US) for 99 years.

Namely, the agreement is genuinely important for upholding the West’s position as a ‘better’ partner for the developing world than Beijing with its profligate loans, or Russia with its willingness to export murderers as military contractors, a trend that has of course turned a lot of heads of African governments in recent years. There is at least a small dent in the argument that the West has a double standard when it comes to recognizing sovereignty disputes at a time where this is important to sustain and garner additional international support for Ukraine. At a time where there is clear hypocrisy on display over the support for Israel and the lack of any costs for its refusal to acknowledge Palestinian sovereignty, this is even more important. But it is also key for pushing back against China.

Beijing undoubtedly has been seeking additional influence in Mauritius, which according to Aiddata has received $1.4 billion in development finance from Beijing for 132 different projects since 2000. Contrary to the concerns that the deal will give Beijing the ability to seek to lease land from Mauritius, the agreement is instead key to keeping Beijing out. That is why the Biden Administration issued a statement so strongly lauding the agreement. The history of secret negotiations over Diego Garcia also raises the prospect of whether another not-so-public deal has been negotiated as part of it to do just that. Another major statement in support also came from India, which is the West’s core partner in countering Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean (in part motivated by its position on Kashmir, whose sovereignty is disputed with Pakistan). New Delhi is also far more influential in Mauritius than Beijing is, due in no small part to the island’s status as a favoured haven for its wealthy and off-shore investment structures.

So the end effect of the Chagos deal is to strengthen the West’s image to crucial ‘in between countries’ in the so-called New Cold War, shore up partnership with Mauritius and other key players in the Indian Ocean, and effectively maintain the status quo with the UK now ‘exercising’ sovereignty rather than retaining it on paper while in reality masking Washington’s effective continued control of a key part of what historian Daniel Immerwahr dubs its ‘Hidden Empire’. From a Western point of view, that seems – to use a Britishism – a cracking deal.