The Impact of One Major U.S. Sanctions Designation in Georgia

Bidzina Ivanishvili sanctioned by OFAC and the risk of secondary sanctions

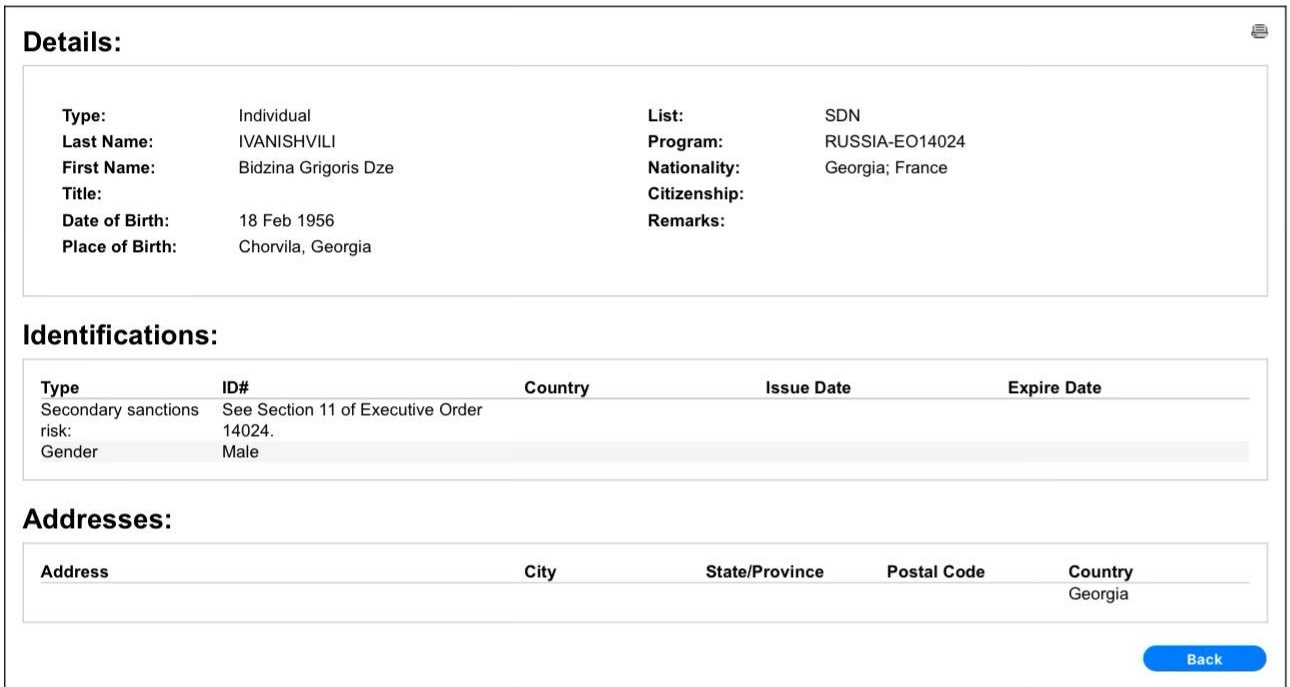

On 27 December, the U.S. Treasury Department’s main sanctions authority, the Office of Foreign Asset Controls (OFAC), announced that it had sanctioned Bidzina Ivanishvili. It used its most far-reaching sanctions tool - the specifically designated nationals (SDN) - and most significantly, it did so under Executive Order 14024, which targets those working on behalf of Vladimir Putin's Kremlin.

The first and most important thing to understand about Ivanishvili’s designation is that it can now be said that - in the view of the U.S. government - is an agent of the Kremlin.

For those unfamiliar with Georgian politics, a brief recap of events leading up to this action before explaining just why the decision to sanction Ivanishvili under E.O. 14024 is so significant.

Ivanishvili has led the Georgian Dream party since it first came to power in 2012. Although he only served as prime minister for the 13 months thereafter and has occasionally claimed to be stepping away from politics since, he has done no such thing. In fact, he dominates the country’s politics, and business, at a level hardly matched by any other individual in any government elsewhere in the world. Ivanishvili is worth around one-third of Georgia’s GDP.

Ivanishvili owns many assets across the country - leading hotels, golf clubs, real estate, to concert venues to banks - though these are largely structured offshore and often list one of his sons as beneficial owners, as do most off his assets abroad (see here, here and here for more). Many others are held through the Cartu Foundation, which bears the same name as a number of his businesses. Ivanishvili also effectively directs the key 'Georgian Co-Investment Fund', which he set up after coming to power in 2012 to support investments in the country. (I recommend this October 2024 Politico long-read on Ivanishvili’s economic and political influence for more.)

His wealth - and the fact that the opposition remains deeply riven by internal rivalries and the complicated legacy of Georgia’s previous dominant politician, Mikheil Saakashvili, president from 2004 to 2013 - helped Georgian Dream win re-election handily in 2016 and 2020. The most recent parliamentary vote, held on 26 October 2024, however, was riven by complaints of vote buying and other electoral irregularities, resulting in fierce criticism from the European Parliament and independent and international election observers as well as polling firms (here, here and here).

At the same time, Ivanishvili has increasingly sought to break with the West over its support for Ukraine and refused to implement sanctions in the country, despite the fact that the vast majority of Georgians overwhelmingly support Kyiv given Russia’s continued de facto occupation of its breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Georgians also make up the largest number of foreign volunteers to Kyiv’s defence, both in sheer and per capita numbers. I wrote two longer pieces on Georgian Dream’s break with the West - for Intellinews and the International Institute for Strategic Studies - which you can read here and here, for more detail.

The initial aftermath of the ‘problematic’ election, however, was fairly muted as the country’s opposition groups lacked any real strategy for opposing the elections. But then Ivanishvili and GD made their biggest mistake since coming to power: Ivanishvili’s latest hand-picked prime minister, Irakli Kobakhidze, announced on 28 November that he was suspending Georgia’s EU accession efforts for four years, in response the European Parliament’s aforementioned criticism of the October Georgian election.

Although Brussels itself had suspended talks with the Georgian Dream government in response to laws it passed earlier this year targeting LGBT rights and civil society - based on similar legislation enacted by Putin’s regime - the move infuriated Georgians across the country. Georgians have overwhelmingly supported both EU and NATO accession for more than 20 years, essentially as long as any independent polling has been conducted in the country, and while Russian threats and skittishness in certain European capitals have kept both out of reach, seeing their own government abandon the effort was a non-starter.

As a result, Georgia has been beset by major protests for the past month. The country has a vibrant and active civil society - precisely why Ivanishvili insisted on passing the foreign agents law after backing down when it was first introduced in 2023 - but while the daily demonstrations that have accompanied other moments of political tensions in past years outside the parliament building in Tbilisi have attracted the most attention, it has been a truly nationwide phenomenon. Georgia’s President Salome Zourabichvili has emerged as the most clear leader from the movement and set up a ‘date with fate’ on 29 December when Ivanishvili’s candidate to replace here - the vocal Western critic and conservative former football player Mikheil Kavelashvili - is set to replace her as president, as she has stated she will not step down until the elections are re-run.

Zourabivhili herself is representative of just how far Ivanishvili has gone. She herself was elected in 2018 with the backing of the Georgian Dream, the last directly-elected president before constitutional changes meant that Kavelashvili was ‘elected’ by the Georgian Dream parliament. But in 2022 she broke with Ivanishvili and his party over their lack of support for Ukraine and of late has taken to calling the party ‘Russian Dream,’ citing its actions in support of Moscow that have included restarting direct flights between Georgia and Russia in May 2023 and turning a blind eye to sanction-evading trade. Ivanishvili and Georgian Dream have only explained their actions by claiming that a conspiratorial ‘global war party’ has been seeking to turn the country into a second front against Russia.

The ongoing protests have raised concerns among Georgia’s business community, even amidst longstanding supporters of the Georgian Dream. The most emblematic example of this came on 25 December when the owner of the Georgian Dream propaganda outlet Imedi TV announced on his chanel that a meeting between business leaders and Kobakhidze two days prior had left even him confused, and that many people find Georgian Dream and Ivanishvili's narrative hard to believe.

To return to the point of this post, however, the risks to the Georgian economy from Ivanishvili’s designation, and the form in which it took, cannot be understated.

By designating Ivanishvili under E.O. 14024, any financial institution that facilitates sanctions evasion is at risk of secondary sanctions, i.e. itself being designated, if it takes action to help evade the sanctions on Ivanishvili. Given his widespread influence, that is no small order. This is a result of another executive order, E.O. 14114, announced by the Biden Administration in December 2023 that authorised sanctions against those who facilitate violations of E.O. 14024, even when there is no immediate U.S. nexus (meaning involvement of a U.S. person or entity, U.S. dollars, or other touchpoint into American jurisdiction). A relatively accessible legal explainer of these ‘secondary sanctions’ is available here .

This marks a major to Georgia’s last major affair with U.S. sanctions designations, which was discussed on this blog in detail last October. That OFAC designation - of former Georgian Dream attorney general and close Ivanishvili family friend Otar Partskhaladze - was met with a remarkable response by the countrys’ central bank, the Georgian National Bank, under clear pressure from Ivanishvili and leading to the resignation of three of its directors, as it moved to effectively shield Partskhaladze from the impact of his OFAC SDN designation, for working as an agent for the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the agency Putin headed before becoming president. Similar action today would risk sanctions under the amended version of E.O. 14024.

Sanctioning Georgia’s central bank would be critical for the country’s economy, and the amended executive order and OFAC explainers make clear that it is at U.S. authorities’ discretion how and when to enforce such secondary sanctions. Georgia’s largest banks already comply with international sanctions - and control the clearing process for other banks to access U.S. dollars - but Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream allies may pressure the country’s key economic actors to choose between the West and Ivanishvili. Indeed, shortly after Ivanishvili’s blacklisting, Prime Minister Kobakhidze praised his boss, describing the move as an ‘award’ for Ivanishvili for defending Georgian interests.

Ivanishvili and his Georgian Dream Party had already made clear to the Georgian people they faced a choice between them and the West with the aforementioned suspension of Georgia’s EU accession efforts. But OFAC’s actions now mean Georgian business must also choose between their country’s dominant billionaire and the West.

Great post. As someone with very little knowledge of Georgian politics, I found this highly informative. Given Ivanishvili's remarkably large presence in the Georgian economy and political system, it appears, from my reading, that adding him to the SDN list is almost tantamount to sanctioning Georgia itself. Would it naturally follow that Georgia should be added to the EU's list of high-risk third countries? To FATF's grey list? I also wondered if there are other countries where a single oligarch/billionaire is so dominant. There's something fascinating to be explored here around extreme income inequality and sanctions exposure.